When Elections are Undemocratic

Why You Should Care about Renovating the Massachusetts Governor’s Council

This week’s Substack is about a government body whose low profile hides surprising power: the Massachusetts Governor’s Council. My goal is to convince you (1) that you should care about this office you may not have heard of, and (2) that its current selection system of insufficiently democratic elections needs renovation.

Check out my remarks on last week’s Progressive Democrats of Massachusetts (PDM) panel discussion, “Demystifying the Governor’s Council.” The panel was also covered by Kristopher Olson of the Massachusetts Lawyers Weekly (paywall).

Why You Should Care about the Governor’s Council

The Governor’s Council is one of Massachusetts’ least-known government bodies. When it does catch public attention, the reasons include fights, scandals, and controversies. A recent spate of such problems has generated some light on the Council—and a trickle of calls to improve it.

Last week, I wrote that (re)designing a government institution should start by clarifying its function. For the Council, its main duties involve “advice and consent” to the governor. This means approving or denying certain gubernatorial actions, like pardons or judicial appointments. (The U.S. Senate exercises “advice and consent” when it votes on Supreme Court nominees.)

The Council can have enormous consequences for people’s lives through this authority. Pardons can grant years or decades of freedom, and a gubernatorially-appointed judge can affect the lives of millions of people through her rulings. Over the course of eight years in office, Governor Baker appointed more than half of the state’s 417 judges. Even more individuals are affected directly by the parole board, whose members must obtain Council approval.

What Virtues Should We Want in a Governor’s Councilor?

These powers all provide a “check” on the governor’s power, usually in high-stakes decisions related to justice. So: Which traits would benefit an officeholder performing this function?

During the PDM event, I offered three virtues:

A councilor with expertise in the Commonwealth’s legal system would be well-suited to ensure that the governor’s decisions serve the public interest. In considering judicial nominees, for instance, she might pay special attention to their qualifications and legal reasoning.

A broadly representative Council could ensure public voice is not overshadowed by expert opinion in legal matters. Councilors could voice widely-held opinions overlooked by legal experts and inject greater popular legitimacy into the legal system.

Political independence could protect matters before the Council from political considerations. A councilor with minimal political ambition or allegiance to other officials may be more likely to act as a “watchdog,” questioning a politically connected appointee—or less likely to torpedo one for political gain.

It is worth noting that expertise and political independence are already baked into nominations and pardons well before the Council is consulted. Still, we might want these virtues to play a role in the final confirmation.

How the Council’s Elections Undermine these Virtues

Unhelpfully, the Council’s elections undermine each of these virtues. This is because their electoral incentives instead reward incumbency and partisanship:

Council races are extremely uncompetitive (as is true in many Massachusetts elections). Since 2000, only 3 Governor’s Council races (out of 96) were decided by less than a 10% margin. Even if voters wanted different outcomes on the Council, they would have little effective opportunity to express that desire.

Some districts are more competitive in primary elections, but incumbents are still the overwhelming favorite. More than half of the 96 elections since 2000 saw no Democratic primary contest at all.

The Council districts are very large, with even more voters than Congressional districts. This makes it harder for candidates to achieve widespread visibility among their constituents.

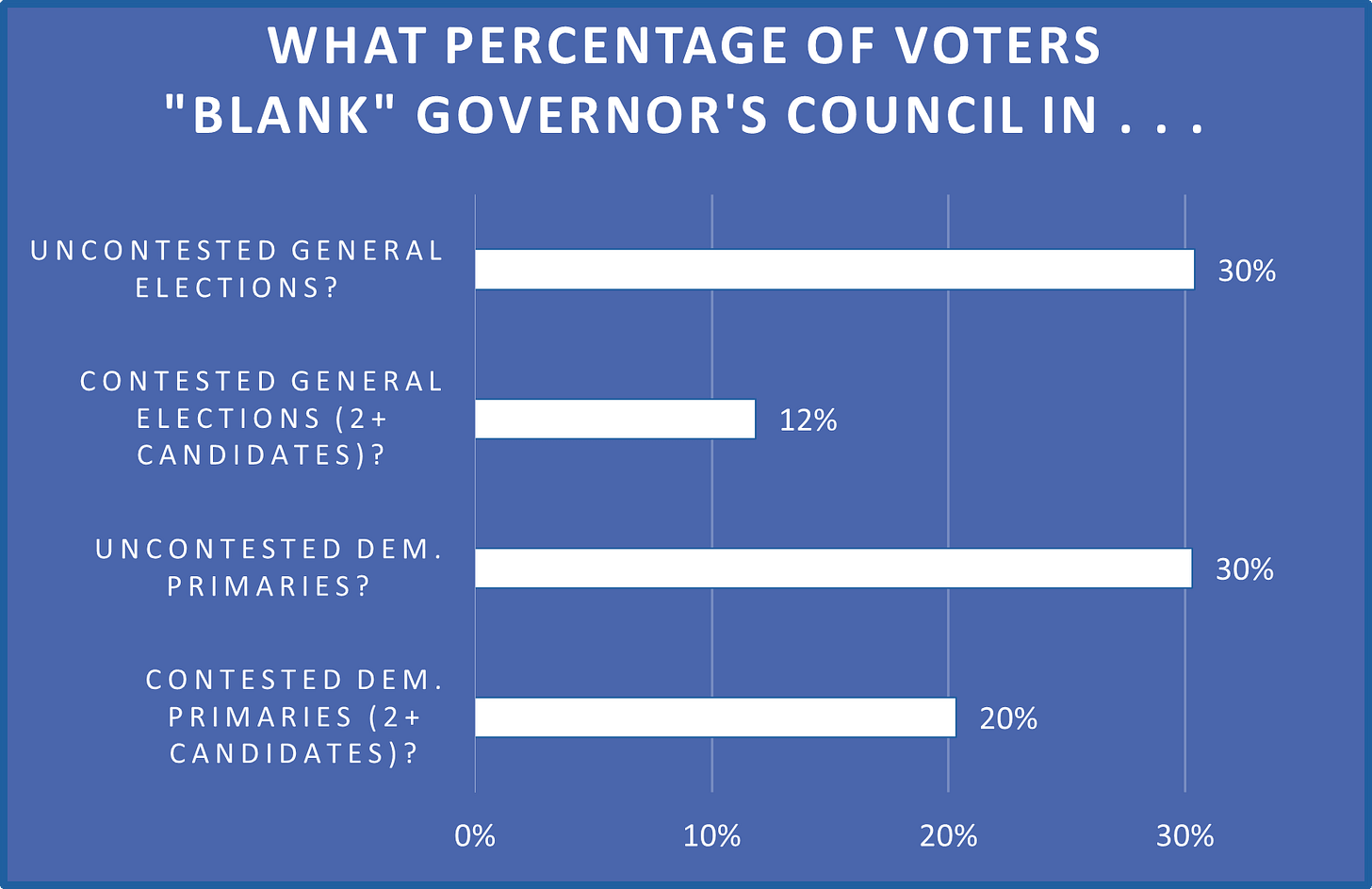

Many voters “blank” the Council, skipping it on their ballot even while voting for other offices, like Congress. This suggests that voters are unfamiliar with the candidates—and will likely weigh incumbency and party affiliation much more heavily.

The election results bear this out: Incumbents have even more advantage here than in other elections, and voters are least likely to blank the Council in races between a Democrat and a Republican. Voters who otherwise are not sure about the Council or its candidates know which party they prefer—and they vote accordingly.

No part of this electoral process necessarily rewards legal expertise: candidates do not need to have a law degree, and some even campaign on their lack thereof giving them “outsider” perspective. Regarding political independence, the Council’s low-profile elections instead favor affiliation with parties and better-known politicians. And as for representation, councilors can hardly claim the affirmative endorsement of broad majorities of their constituents. Turnout is generally low, blanking is high, there is little coverage of the Council to inform public opinion, and the more-competitive primary elections feature both lower turnout and a less representative electorate.

To distill the problem: The Council’s elections do little to improve representation or accountability. To the extent that any councilor displays expertise, represents the broad public, or acts as an independent watchdog (as many certainly do), she does so despite electoral incentives.

What Could Reform Look Like?

Given that low-salience, low-turnout elections undermine the virtues we would want in the Governor’s Council, the next question is: What selection mechanism would do the job better? I see three possible answers:

Increase the Council’s profile. If voters had a better idea of what the council does and what the candidates stand for, its elections could become more competitive. This would address many of the present misalignments between the elections and the Council’s function.

Move its functions to a better-known body. In many states, “advice and consent” belongs to the legislature. There are reasons why I don’t think this is the best solution here, but it would at least mean that voters (especially primary voters) would be more likely to recognize the candidates hoping to fulfill the Council’s current function.

Choose the Council by a mechanism other than elections: At the PDM event, I asked if we would get a worse outcome if we picked the Council out of a hat? More seriously, one way to achieve representation and independence would be to remove the Council from the electoral process altogether. We could instead choose Councilors like we choose juries, using a process called “sortition.” Councilors could be selected from among all registered voters—or, if you wanted legal expertise, from all lawyers admitted to the Massachusetts Bar.

Next week, I will make an argument for renovating the Governor’s Council using this third model, sortition. Such a reform would require a Constitutional amendment, so its success would be far from guaranteed. My goal, though, is to show how it solves the specific design flaws currently plaguing the Council—which is how I think we should approach democratic reforms more generally.

At the very least, the long process of a Constitutional amendment would generate some coverage for the Council. If nothing else, that would be a victory.

Thank you for reading – and happy Memorial Day weekend!